Convict Valley

The Convict Valley by Mark Dunn is well researched and beautifully written. Dunn was born in Singleton, of convict forebears, and his love for the Hunter Valley, with its natural beauty, Aboriginal heritage and settler history, is evident from his text. The first European contact with the area occurred in 1790, when five convicts stole a boat, sailed to what is now Port Stephens, were taken in by aborigines, begot children and lived happily until discovered in 1795 and returned to Sydney. Lieutenant Shortland is credited with the 1797 discovery of the Hunter River with its capacious harbour, as well as coal, cedar trees and shell middens. The place became a convict outpost after the Irish Castle Cove rebellion of 1804, and for a time the most troublesome convicts were sent there. The story from then on is one of exploitation of the coal, the cedar and the native inhabitants. Dunn’s epilogue mentions the death in 1902 of 85-year-old Phillip Kelly, a well-respected citizen and local historian. Dunn’s grandmother, who was Kelly’s daughter, remembered seeing on his back the scars from his floggings—he had been transported at the age of 15 in 1834.

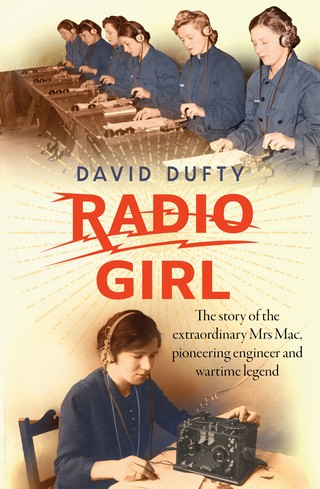

David Dufty’s Radio Girl is a biography of Violet McKenzie—a.k.a. Mrs Mac— Australia’s first woman electrical engineer. Mrs Mac had many projects and interests, including corresponding with Albert Einstein, running a wireless radio pioneer business and founding the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps (‘Sigs’), which trained hundreds of women in Morse Code and Semaphore using her unique system of musical mnemonics. By the end of WW2 the women of Sigs had trained twelve thousand Australian and other allied servicemen in signalling. Mrs Mac did all of this gratis and, though she was a living legend to the troops, she was soon forgotten in peacetime. She was, above all else, a firm feminist and when, as a prime mover in the formation of the WRANS, she was asked in an interview with a gaggle of admirals ‘What about sex?’ she assured her questioner that ‘There have never been any goings-on’. Dufty thinks it is time that Australian feminists reclaimed this trailblazer who, though tiny in stature, always stood her ground against bullies in the armed forces and elsewhere. Before she died at the age of 91 she said ‘I have proved to them all that women can be as good as, or even better, than men.’ Dufty’s 2017 book, The Secret Code Breakers of Central Bureau, about the clever women and men who deciphered Japanese wartime codes, included a chapter on Mrs Mac. This was so popular with his readers that he followed up with Radio Girl. Inspiring.

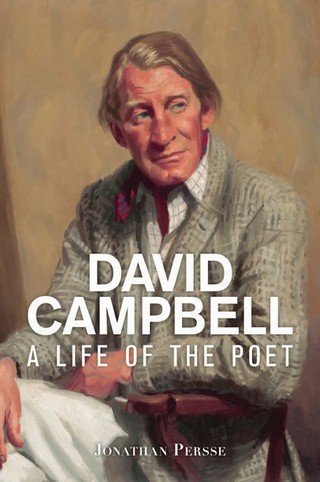

David Campbell (1915–1979) was one of the great fellowship of Australian poets which emerged after WW2 and included A.D. Hope, Douglas Stewart, Judith Wright, James McAuley, Gwen Harwood and Rosemary Dobson. In David Campbell: A Life of the Poet, Jonathan Persse has given us an impressive biography of Campbell which illustrates his life with a generous selection of his poems. Persse tells us that he was ‘handsome, warm, personable, confident, charming, gregarious and easy-going in his manner’. Born into a pastoral family, Campbell was educated at The King’s School, where Persse himself later taught, and at Cambridge University. While he excelled there at rugby, his professors noted his gift for lyric poetry with its obvious allusions to Elizabethan love poetry. After serving notably well in the RAAF during the war, he returned to the land in NSW, not far from Canberra—an excellent place for meeting other poets. Both Jonathan Persse’s book and David Campbell’s poems are highly recommended: if you acquire this book you’ll have both.

Much to my surprise, I greatly enjoyed Malcolm Turnbull’s A Bigger Picture— even the political bits. The man is a born writer. I opened his book to catch up on the more intimate details of our most recent coup and three hours later I was still engrossed. Above all, I finished it! Malcolm loved his mother Coral Lansbury, but it was his father who took him walking on the sand at Bondi, curing his pigeon toes and helping him cope with his asthma. After the break-up of his parents’ marriage his father and he were, he says, like brothers. His lowest point was when he was sent to a boarding school at the age of eight after his mother had gone away. His highest is surely his defence in the NSW Supreme Court of the publisher of Peter Wright’s MI5 memoir Spycatcher, when at the age of 32 he interrogated one of Mrs Thatcher’s senior civil servants, making him look like a ‘wally among the wallabies’. In his chapter Defending the Goanna, he gives a sparkling account of his 1980s skirmish with the Costigan Royal Commission in defence of the good reputation of the late Kerry Packer. Mr Turnbull has been barrister, solicitor, journalist, businessman, investment banker, and one of the leading advocates for an Australian republic, but, in the opinion even of some well-wishers, he should not have entered politics. However, he himself considers that he achieved much as PM and, as one would expect, argues his case pellucidly. Even if you’re a leftie like me, don’t let Mr Turnbull’s politics put you off. Every chapter of his book is action-packed. In particular, his version of his negotiations with President Trump over iron ore tariffs borders on the hilarious. But for me, the best thing he did was to invite The Guardian newspaper to Australia. Sonia